Brokerage firm Robinhood celebrated its initial public offering (‘IPO’) on Thursday, July 29th, listing its shares for purchase on the NASDAQ with the ticker HOOD. It then -

NO! Shoo hipster.

As we were saying, Robinhood was offered to the public for the first time last Thursday at $38 per share. It then promptly lost money for the next five days, dropping from its IPO price of $38 per share down to as low as $33.25 before recovering back to $37.59 per share by Tuesday this week.

Now, it’s going on a tear, cranking up over 60% as of this writing:

Trading has gotten so crazy the exchanges triggered a circuit-breaker which temporarily stops stocks from trading when they are wildly up or down. It’s meant to cool the raging passions of the market. It’s like the exchanges saying ‘ow, you’re on my hair’ before resuming the action.

That feeling in your chest right now is the fear of missing out (‘FOMO’) and it’s a common diagnosis when a hot stock pops (or it could be that spicy sausage breakfast burrito; too soon to tell. Grab a Pepcid and chill).

In reality, HOOD is trading like a typical IPO: the average first-day “pop” was 38% in 2020. Just-IPO’d stocks tend to be very volatile out of the gate. The good news is that there are plenty of opportunities to get on board later.

What is an IPO anyway?

An IPO is an ‘initial public offering.’ As the name implies, it’s the first time that shares in a previously private company are offered for the public to purchase. Private companies choose to go public for two reasons: to raise money from investors to finance their ongoing operations and to create a liquidity event for the founders, key employees, and early investors.

Raise money. An IPO is a big step for the previously private company, in no small part due to the rigorous reporting requirements imposed by the Securities and Exchange Commission (‘SEC’), the regulatory body that oversees capital markets. Firms must disclose a laundry list of items including history, organizational structure, financial statements, earnings per share, subsidiaries, executive compensation, and any other relevant data on a standardized form.

So, every meeting you’ve ever been in where the organizational chart makes an appearance – yeah, now everyone gets to see that.

Company’s subject themselves to these rigorous reporting requirements in large part to secure more favorable financing terms. Which is a big deal. Who would you feel more comfortable lending money to? The person with a sterling credit report or the person who says, ‘just trust me?’

Liquidity event. The other reason to pursue an IPO is to create a liquidity event for the founders, key employees, and early investors. It takes a lot of stress, commitment, and capital to grow a company from a garage to a fully-operational battle station.

The value of a private company’s shares is like the value of your house. Zestimate’s aside, the only proper valuation of your home takes place when you hire an appraiser. You could appraise your home regularly, but… why? The appraisal is only worth it when you want to sell the home.

An IPO is like putting your house up for sale and having the public bid on it. For the key employees and early investors, the IPO is an opportunity to sell their part of the house. And, if they choose to retain any shares in the company (which most do), they go from getting an annual appraisal of their shares’ value to seeing the value on a by-the-second basis. Their piece of the company grows more valuable if the stock price goes up, and diminishes if the stock price goes down. Since the shares are now liquid, it gives the key employees and early investors control over when they choose to cash out, and at what price.

So, an IPO is an opportunity for the company to raise money to keep growing, and for the key employees and early investors to get pay-yayed.

It’s too soon to know Robinhood’s fate. Despite the hot start, the odds aren’t in their favor. That might be surprising to hear, but most stocks are actually terrible investments, relative to just investing in an index fund.

One study looked at the lifetime returns of every stock on the Russell 3000 index - so, over 3,000 stocks - over the period of 1983 to 2006. What they found might surprise you:

39% of stocks had a negative lifetime total return (2 out of every 5 stocks are money-losing investments)

18.5% of stocks lost at least 75% of their value (nearly 1 out of every 5 stocks is a really bad investment)

64% of stocks underperformed the Russell 3000 during their lifetime (most stocks can’t keep up with a diversified index)

A small minority of stocks significantly outperformed their peers (capitalism yields a minority of big winners that all have something in common)

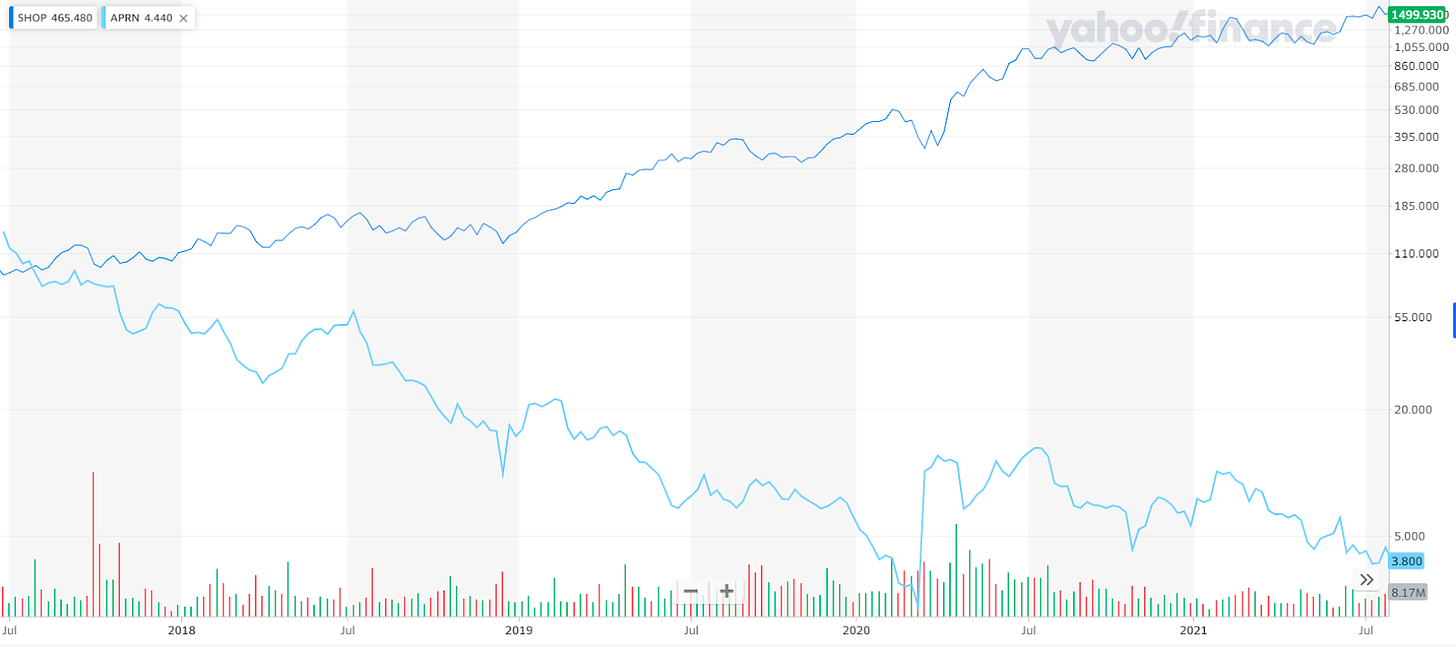

In other words, for every one Shopify, there are five Blue Aprons:

What’s the upside?

IPOs attract a lot of attention from the Street, from fawning financial media, and from retail investors. When the headlines blare how well a new stock is performing, the FOMO can be nausea-inducing. Our advice: wait to chase the hot thing until it’s cooled off a bit. Keep it simple and stay diversified.

Not only is it expensive to get in early on an IPO (38% avg gain on the first day) but 65% of IPOs have underperformed the broader market! Unless you are the founder of the company, an early employee, or a venture capitalist, stay away from IPOs.

Just #pepcidandchill.

For Your Weekend:

This is where we’ll post a round-up of essays, podcasts, and streaming shows to check out over your weekend. We cast a wide net so you don’t have to.

Read:

Persuading the Body to Regenerate Its Limbs by Matthew Hutson (The New Yorker)

Deer can regrow their antlers, and humans can replace their liver. What else might be possible?

Some of the most important discoveries of his career hinge on the planarian—a type of flatworm about two centimetres long that, under a microscope, resembles a cartoon of a cross-eyed phallus. Levin is interested in the planarian because, if you cut off its head, it grows a new one; simultaneously, its severed head grows a new tail. Researchers have discovered that no matter how many pieces you cut a planarian into—the record is two hundred and seventy-nine—you will get as many new worms.

The Sun Gods of the LBC by Jeff Weiss (The Ringer)

Twenty-five years ago, Sublime released their third album, a sprawling magnum opus of sunburned ska, punk, reggae, and stoner anthems that turned three kids from Southern California and a Dalmatian into legends. This is the story of how it came together, the tragic end of the band, and why the songs still live on.

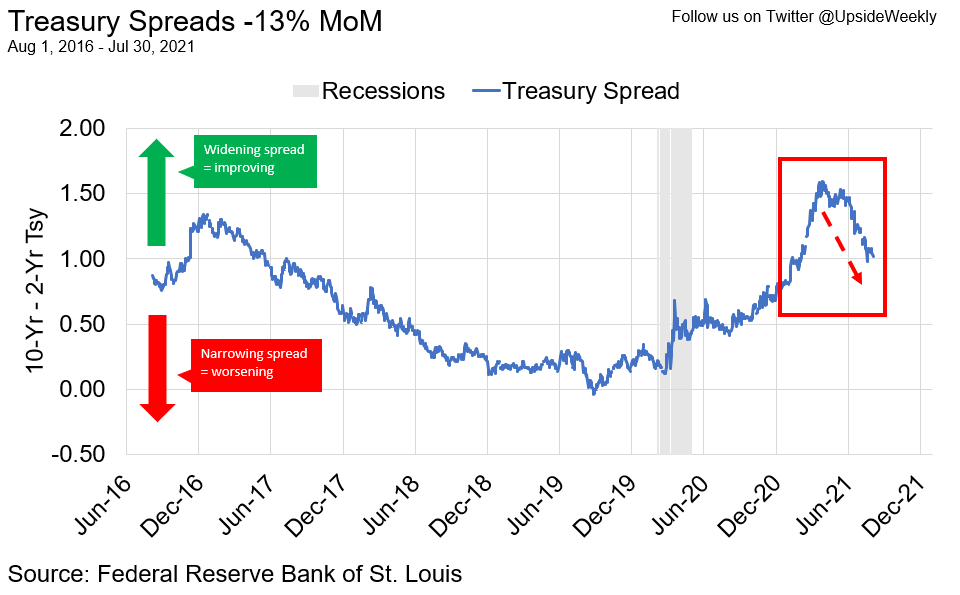

INFLATION WATCH! August 2021 by Jack

July is in the books! Economic conditions appear to be improving, though the bond market may be flashing some warning signs.